COVID-19: Entering Phase 2: Moderna Therapeutics Races Vaccine: More than 02 (two) months after the WHO – World Health Organization officially declared the Covid-19 the new Coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, experts trying to envision ways to safely return life in the United States to normal have agreed that having a vaccine is a crucial component of any plan.

COVID-19: Entering Phase 2: Moderna Therapeutics Races Vaccine

The new coronavirus or simple COVID-19 pandemic has claimed the lives of 283,271 worldwide, with more than 04 (four) million confirmed cases in more than 200 countries.

Moderna Therapeutics, a Cambridge-based biotechnology company founded in 2010, is now at the forefront of the new coronavirus vaccine development. The company recently received FDA approval to move onto Phase 2 of vaccine testing, in addition to 500 million dollars’ worth of grants from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, a government organization that assists companies through the development process of drugs and vaccines.

The company employs messenger RNA to create medicines that enable a patient’s cells to create proteins to treat disease. Messenger RNA — dubbed “the software of life” on the company’s website — provides instructions to cells to make proteins for various functions in the body.

Timothy A. Springer, a professor at Harvard Medical School and founding investor in Moderna Therapeutics, said his fellow faculty member, Derrick J. Rossi, asked him if he would be interested in investing in a company using Rossi’s research on modified RNA.

“Modified RNA seemed a very exciting new technology with lots of potential,” Springer said.

“I said, ‘Yes, I would love to invest, and I’d also like to help you get it started.’”

“Derrick Rossi — who was a professor at Harvard, a young professor — he had made a finding about how you could add certain types of RNA to cells and make them kind of like what’s called a stem cell,” Robert S. Langer, a co-founder of the company and professor at MIT, said.

Rather than just using this strategy for what Langer calls “tissue engineering,” Langer suggested using it for drugs and vaccines as well.

“One of the beauties of messenger RNA is that you can make it and you can make it quickly,” Langer said. “But then what happens is you can just inject a little bit of it in a nanoparticle, you inject it into the body, and then the body is actually the factory that makes it.”

Entering Trials – Vaccine for Covid-19

According to the World Health Organization, there are currently eight candidate coronavirus vaccines in clinical evaluation. Moderna is one of the first companies to receive approval for Phase 2 of clinical evaluation.

The National Institute of Health announced in late March that it would begin Phase 1 study of Moderna’s vaccine.

“There were 45 healthy volunteers. The NIH ran the trial, and that trial is still proceeding, but they expanded the population of what was prior — healthy 18- to 55-year-olds — has now been expanded to include 56- to 70-year-olds and 71-year-olds and above,” Raymond C. Jordan, the head of corporate affairs for Moderna, said in an interview with The Crimson.

“We’ve also been cleared by the FDA to enter what’s called a Phase 2 trial. And that trial will go into hundreds — roughly 600 healthy volunteers — across the full spectrum of age from 18 years old, right up through the older and elderly population,” Jordan added.

Moderna is also already scaling up its own production capacity and partnering with a manufacturing organization to further increase capacity.

“We’re doing this before having all of the final efficacy data that we would want from the earlier trials,” Jordan added.

Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel said that, in a best case scenario, people may be able to start receiving vaccinations as early as September.

“This is a timeline assuming everything goes well. Any bumps on the road would just push the time out obviously,” Bancel said.

“Last week we got the green light from the FDA to start the Phase 2, around 600 subjects, and the plan is to start the Phase 3 early summer.”

“We’re expecting to be able to make up to tens of millions of doses a month this year, and as many as a billion doses in 2021,” Jordan said.

Barry R. Bloom, a professor of immunology and global health at the School of Public Health, explained that the process of development, approval, and mass production for vaccines traditionally takes much longer. The fastest vaccine was for mumps and rubella, which took four years, while other vaccines — like varicella, which took 27 years — have taken much longer.

But according to Bloom, even before the pandemic, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority had been coordinating an expedited vaccine approval process with the National Institute of Health.

“The unique part of BARDA was that it not only dealt with scientists, which is what NIH largely does — it dealt with 300 companies. So that becomes a way to save another major problem in the timeframe,” said Bloom, explaining that the need to mass produce so many doses in so little time presents significant difficulties.

Moderna has benefited from this expedited process.

“In 65 days, they [Moderna] had the vaccine from the DNA sequence, cDNA sequence, healthy RNA, to getting the first shots into Phase 1 — people’s arms — which is astonishing and unprecedented,” Bloom said.

Though Moderna is among several companies racing to develop a vaccine, Springer — the Medical School professor — said Moderna brings something to the table the others do not.

“I think Moderna does have a very strong advantage over the rest of the field,” he said. “It’s multifold. They have hugely invested in the technology underlying RNA science, which hasn’t really previously been studied throughout industry.”

“They’re using modified RNA,” he said. “It requires a very deep understanding.”

Thoughtful recruiting was key to Moderna’s efforts, Springer said, adding that biochemist and molecular biologist Melissa J. Moore, whom he described as “one of the most outstanding RNA scientists in the world,” serves as the company’s Chief Scientific Officer.

‘NOT OUR FIRST RODEO’

In addition to technology, Bancel said that Moderna’s team has valuable experience in developing vaccines quickly, including against MERS, another coronavirus.

Bancel said his team has already shown “the ability to move very, very fast.”

“It was not our first rodeo — this is our tenth vaccine to go into clinical studies,” he added.

Noubar B. Afeyan, another co-founder of Moderna, explained how the company must adapt its operations during this new project.

“This has, in a significant way one could argue, interrupted many things and required a lot of resource allocation, the scarcest version of which is our management attention,” Afeyan said. “We are implementing processes as a company that would usually be necessary much later in the development, but we have no choice because we’ve been thrust into that mode sooner.”

Indeed, Bancel said his team has been working hard to adapt to these unusual times.

“Often we get emails at two o’clock in the morning or on weekends,” Bancel said. “People are working very hard — the team at Moderna has been — seven days a week.”

There is some concern over what would happen if the current strain of coronavirus were to mutate, but Jordan and Langer feel the vaccine could be easily adapted.

“If you think for instance of the flu — the sort of annual flu, the seasonal flu vaccines — once you’ve got the platform for addressing it, you can change it each year without having to go through a full process of clinical trials,” Jordan said.

Bloom emphasized the importance of successfully developing a vaccine in order to end the pandemic.

“Historically, the only way to interrupt that timeframe, which is dictated by the virus, is to have a vaccine that interrupts transmission and provides immunity. That’s it,” he said.

“There are no other alternatives.”

—Staff writer Natalie L. Kahn can be reached at [email protected].

—Staff writer Taylor C. Peterman can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @taylorcpeterman.

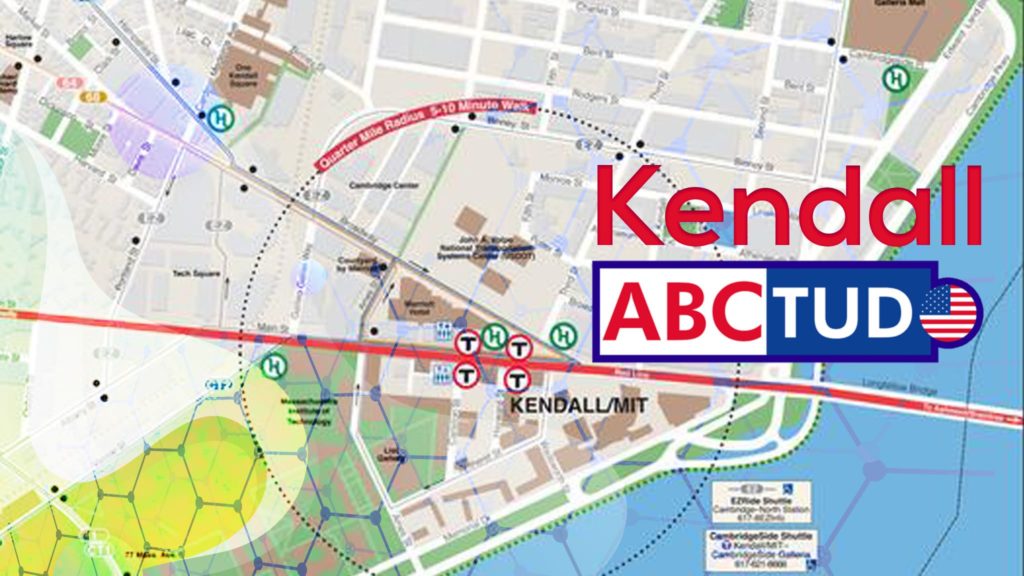

Kendall/MIT station

Kendall/MIT is an underground rapid transit station in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It serves the MBTA Red Line, Located at the intersection of Main Street and Broadway, it is named for the primary areas it serves – the Kendall Square business district and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Opened in March 1912 as part of the original Cambridge Subway, Kendall/MIT has two side platforms serving the line’s two tracks. The Kendall Band, a public art installation of hand-operated musical sculptures, is located between the tracks in the station with controls located on the platforms. Kendall/MIT station is fully handicapped accessible.

History of Kendall Station

The Cambridge Subway opened from Park Street Under to Harvard on March 23, 1912, with intermediate stops at Central and Kendall. From the early 20th century through the 1970s, the MBTA operated a powerhouse above ground in Kendall Square, including rotary converters (also called cycloconverters) to transform incoming AC electrical power to 600 volts DC power fed to the third rail to run the subway. An old-fashioned cycloconverter consisted of an AC motor coupled to a huge, slowly rotating flywheel coupled to a DC generator, hence the name. Despite the development of compact low-maintenance semiconductor-based power rectifiers, the long-obsolete electromechanical technology still occupied prime real estate in the heart of Kendall Square. The MBTA powerhouse was demolished, and replaced with an office building located at the convergence of Broadway and Main Street.

Name Changes and Reconstruction

The MBTA has renamed the station on several occasions. On August 7, 1978, the station was renamed as Kendall/MIT to indicate the nearby presence of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. On December 2, 1982, Columbia station was renamed JFK/UMass, and Kendall/MIT was renamed as Cambridge Center/MIT after the adjacent Cambridge Center development, although most station signs were not changed.

There were many complaints that the MBTA had suddenly changed the name without public input, and that the new name would be confused with the next Red Line station at Central Square. On June 26, 1985, the name was reverted to Kendall/MIT.

During the 1980s, the MBTA rebuilt Kendall/MIT and other Red Line stations with longer platforms for six-car trains and with elevators for handicapped accessibility. The rebuilt station was dedicated in October 1987 and six-car trains began operation on January 21, 1988